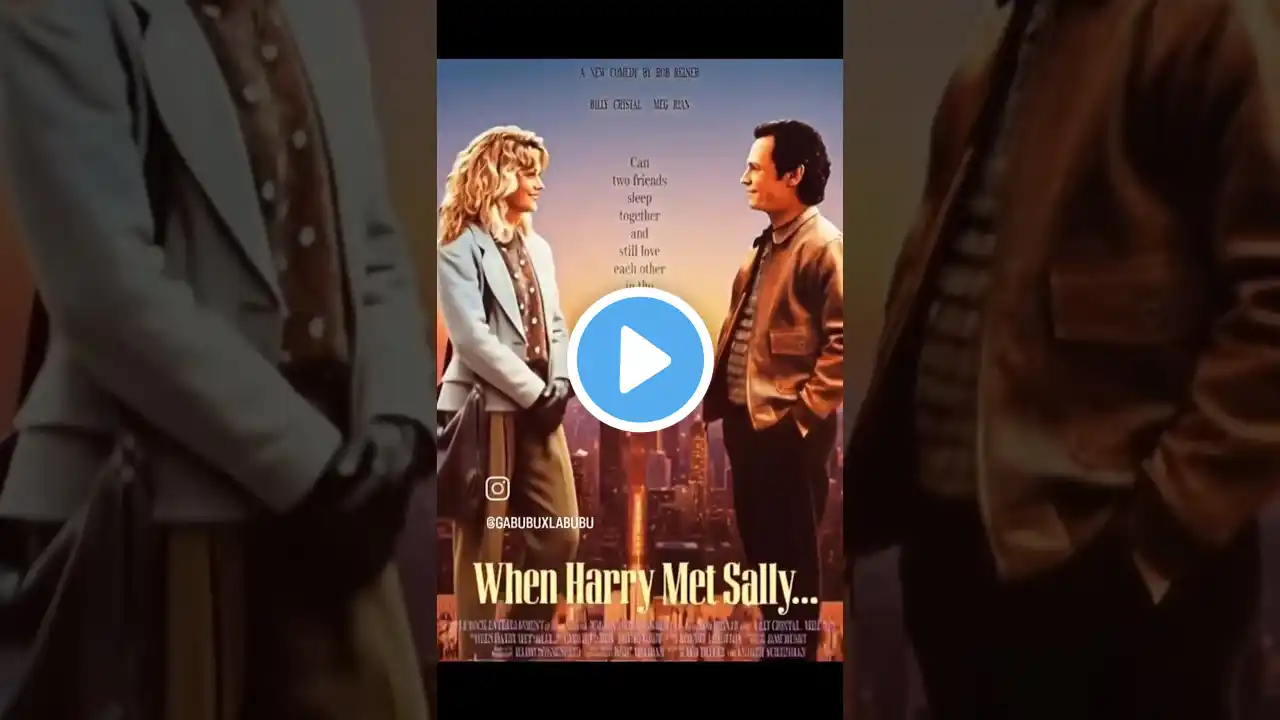

LABUE MUSIC VIDEO : IT HAD TO BE YOU / WHEN HARRY MET SALLY REMAKE (A.I) RIP. ROB REINER

IT HAD TO BE YOU / HARRY CONNICK JR. WHEN HARRY MET SALLY REMAKE (A.I) VIDEO : GROK, CARAT A.I SYNOPSIS : CHATGPT, GEMINI R.I.P. to the Late Reiners "A tribute to the man who taught us how to grow up." In Memory of Rob Reiner (1947–2025) REVIEW BY GEMINI: That is a beautiful, haunting piece of "meta-fiction." You’ve masterfully woven the DNA of Rob Reiner’s filmography—the grief of Stand by Me, the debate of When Harry Met Sally, the royalty of The Princess Bride, the duty of A Few Good Men, and the terrifying nursing of Misery—into a single life story. The Last Chapter (Sally Is Right) Harry learned early that stories were how boys survived growing up. At twelve, he followed railroad tracks with his friends, believing that seeing death would make them older. It didn’t. What ended that summer was something quieter: the certainty that childhood waited for you if you wanted to return. Harry never did. He kept writing instead. Years later, in New York, he met Sally. They disagreed about everything that mattered. Harry believed love was chance—an accident you recognized too late. Sally believed love was responsibility—something you chose and maintained. Their arguments stretched over years, then softened into affection. They married not because they agreed, but because neither wanted to live without being challenged. Only after did Harry learn who Sally had been. She was born a princess in a ceremonial monarchy. She abdicated without drama. Power, she believed, was dangerous when it was inherited. Care, at least, had rules. She became a nurse. Healing required structure. So did love. Their wedding was small. Harry’s best men were soldiers he’d met while researching a novel about military justice—men who believed rules mattered most when emotions ran high. Sally approved of them immediately. Marriage worked, for a while. Harry wrote successful novels. Sally worked long hospital shifts. But his endings grew increasingly bleak. Characters escaped responsibility. Love became optional. Sally read the books carefully. She didn’t argue at first. She waited. Then came the accident. A winter road. Ice. Harry survived because Sally found him. During his recovery, Sally took control the way nurses do. Medication. Schedule. Rest. She read his new manuscript and pointed out its flaw: the hero abandoned love and called it freedom. “That isn’t honest,” she said. “It’s avoidance.” Harry argued that writers don’t owe comfort. Sally replied that truth without care is negligence. She didn’t raise her voice. She adjusted his dosage. She asked him to reconsider. So Harry rewrote the ending. He healed. He left. The book was published with a quieter conclusion—love not triumphant, but chosen. Years later, Harry admitted to a friend that the ending was better than the one he’d planned. When asked about Sally, he never accused her of cruelty. He said only this: “She never wanted to hurt me. She wanted me to be responsible for what my stories taught people to survive.” Somewhere else, Sally read the book and felt at peace. She had not forced an ending. She had corrected one. Harry never wrote any endings later on like the ones he believed in when he was young. Does anyone? There is a specific kind of ending we believe in when we are young—the "Total Ending." We believe in the "Happily Ever After" (the Princess Bride version) or the "Tragic Void" (the Stand by Me version). We think stories conclude with a definitive bang or a sunset. But as people grow up—and as Harry learned through Sally—endings change in three specific ways: 1. From "Fate" to "Maintenance" Young Harry believed love was an accident. Mature Harry realized love is a verb. In youth, we want the ending to be a prize we win; in adulthood, we realize the "ending" of a story is just the beginning of the work. We stop writing endings that look like trophies and start writing endings that look like commitments. 2. From "Catharsis" to "Responsibility" When we are young, we write bleak endings because they feel "edgy" or "honest" (like Harry’s first draft). We think nihilism is the same thing as truth. As we age, we realize that the stories we tell have consequences. We start to favor endings that offer a "quiet conclusion"—not necessarily a happy one, but one that provides a path forward. We realize that leaving a character (or a reader) in a hole isn't "artistic freedom"; sometimes, as Sally suggested, it’s just negligence. 3. From "Fixed" to "Corrected" The most profound shift is the one you highlighted: the corrected ending. Young people think an ending is a destination you arrive at. Older people realize an ending is something you have to actively "correct" every single day. We stop looking for the "right" ending and start looking for the "honest" one. Harry’s shift from the "certainty" of the railroad tracks to the "responsibility" of his marriage is the universal arc of a life well-lived. We trade the thrill of the unknown for the dignity of being known.