ASD closure up.

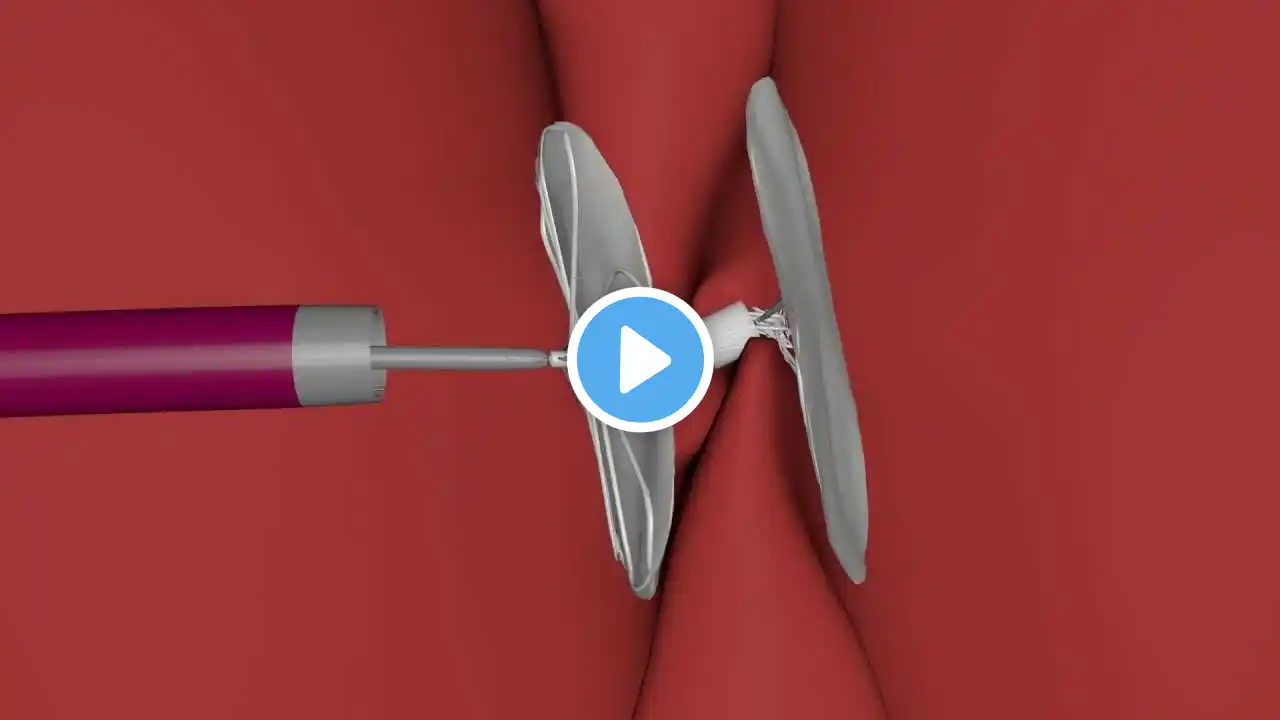

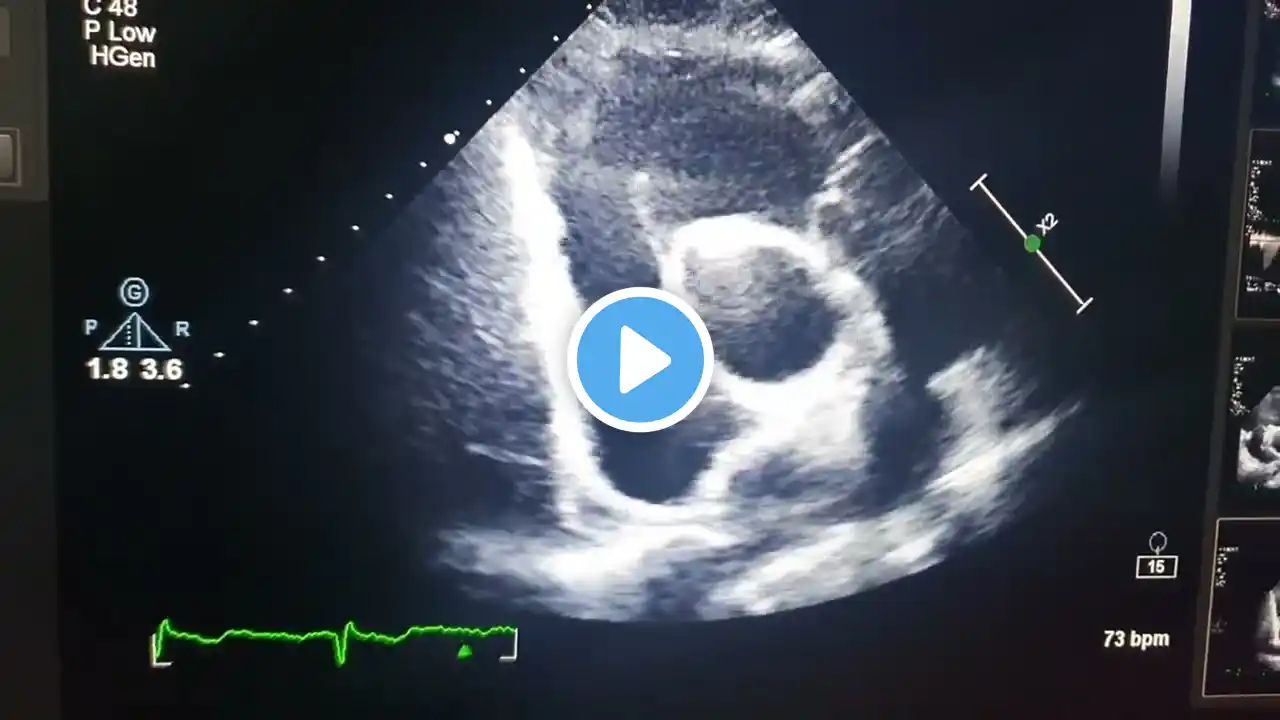

ASD closure is a procedure to close an atrial septal defect (ASD) or hole in your heart. An atrial septal defect (ASD) is an abnormal opening in the wall (septum) between your heart’s two upper chambers (atria). Every baby is born with a small opening there. The hole usually closes a few weeks or months after birth. But sometimes a baby is born with a larger hole that doesn’t close properly. If the hole is small, it may not cause any problems or need treatment. But if the ASD is large, it can allow blood to leak into the wrong chambers of your heart. This can make your heart and lungs work harder, causing symptoms and complications, including: Abnormal heart rhythm (arrhythmia) like atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter. Enlarged heart. Heart failure. High pressure in your lungs (pulmonary hypertension). Shortness of breath. Stroke. Your healthcare provider may suggest ASD closure if you’re at risk for those complications. They also might recommend the procedure if you’re already having surgery for another congenital heart defect. Surgeons often perform ASD closure on young children to avoid future heart damage and complications. ASD closure is performed by a heart surgeon or interventional cardiologist, both specialists in heart procedures. There are several techniques for ASD closure. It may require open-heart surgery. Sometimes, it can be accomplished with a minimally invasive procedure called cardiac catheterization using a catheter threaded from a vein in your groin up to your heart. Covered by a patch made of synthetic material or your own tissue, taken from another area of your heart. Plugged with a closure device. Sewn shut with sutures (stitches). Your healthcare provider will recommend the appropriate technique for you, depending on: Any other heart conditions you may have. The size and location of the hole. Your overall health. Some medical facilities even use robotic-assisted surgery to repair an ASD. During surgery for ASD closure, you’re under general anesthesia. You receive medications that put you to sleep, so you feel no pain during the operation. A healthcare provider connects you to several machines that monitor your vital signs, including heart rate and breathing. They also connect you to a heart-lung machine to take over the work of your heart during the procedure. Your heart surgeon makes an incision (cut) in your chest. Your surgeon may make the incision: Down the middle of the chest over your breastbone. On the right side of your chest. In another location determined by your surgeon. Your surgeon then uses a special tool to spread your ribs. Using an endoscope, a thin tube with a light and camera at the end, your surgeon locates the ASD. Then they close it with a plug, patch or sutures. If you have a smaller ASD and no other heart conditions that need correcting, you may be able to have transcatheter ASD closure. This method is less invasive and generally makes recovery easier and faster. For transcatheter ASD closure, you may receive general anesthesia or medications that sedate you. Sedation makes you sleepy and relaxed, but you’re still conscious (unlike general anesthesia). To perform a transcatheter ASD closure, your interventional cardiologist: Makes a small incision in the femoral vein and sometimes also a femoral artery in your groin. Inserts a thin tube called a catheter, which holds the closure device on the end. Uses imaging technology such as X-ray and echocardiogram to guide the catheter and device through the vein to your heart. Places the closure device into the hole. Removes the catheter. After ASD closure, your healthcare team monitors you as you recover from anesthesia. They also take images of your heart to make sure the procedure was successful. You typically stay in the hospital for one or more nights, depending on the type of procedure you had. ASD closure can reduce the symptoms and complications associated with a hole in your heart. This can protect your heart and lungs, helping you live a longer, more productive life. ASD closure is usually safe and effective, but it does carry some risks, including: Allergies to materials used during the procedure. Abnormal heart rhythm (arrhythmia). Bleeding, which may require a blood transfusion. Damage or puncture of heart tissue or veins, requiring surgical correction. Infection of the incision or around the closure device. Kidney failure. Stroke or transient ischemic attack (mini-stroke). Some complications can be life-threatening.