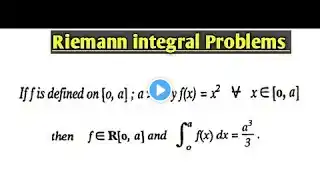

Riemann Integration Part - VI

an arbitrarily chosen point in [xᵢ₋₁, xᵢ]. The document emphasizes that, for this sum, the function 'f' does not need to be bounded. A function 'f' is said to be Riemann integrable if the limit of S(P,f) exists as the norm of the partition ||P|| approaches 0. This means there exists a number A (called the Riemann integral) such that for every ε greater than 0, there is a δ greater than 0, where ||P|| less than δ implies |S(P,f) - A| less than ε for every choice of cᵢ. A significant part of the lecture is dedicated to proving the theorem: If f:[a,b]→ℝ is Riemann integrable, then f is bounded. The proof starts by assuming f is Riemann integrable, meaning there exists an A such that for a given ε and δ, |S(P,f) - A| less than ε for any partition P with ||P|| less than δ and any choice of points cᵢ. By considering two different choices of points (sᵢ and tᵢ) within the sub-intervals and subtracting the corresponding Riemann sums, the lecture derives that |Σ (f(sᵢ) - f(tᵢ))(xᵢ - xᵢ₋₁)| less than 2ε. By selectively choosing sᵢ = tᵢ for all sub-intervals except the first one (i.e., for i ≥ 2), the inequality simplifies to |f(s₁) - f(t₁)|(x₁ - x₀) less than 2ε. Further manipulation using triangle inequality and bounding the interval length helps to show that |f(s₁)| is less than or equal to a constant M, effectively proving that f is bounded in the first sub-interval. This process can be generalized to show that f is bounded in every sub-interval [xᵢ₋₁, xᵢ], and therefore, f is bounded over the entire interval [a,b].