Evolutionary Process Models

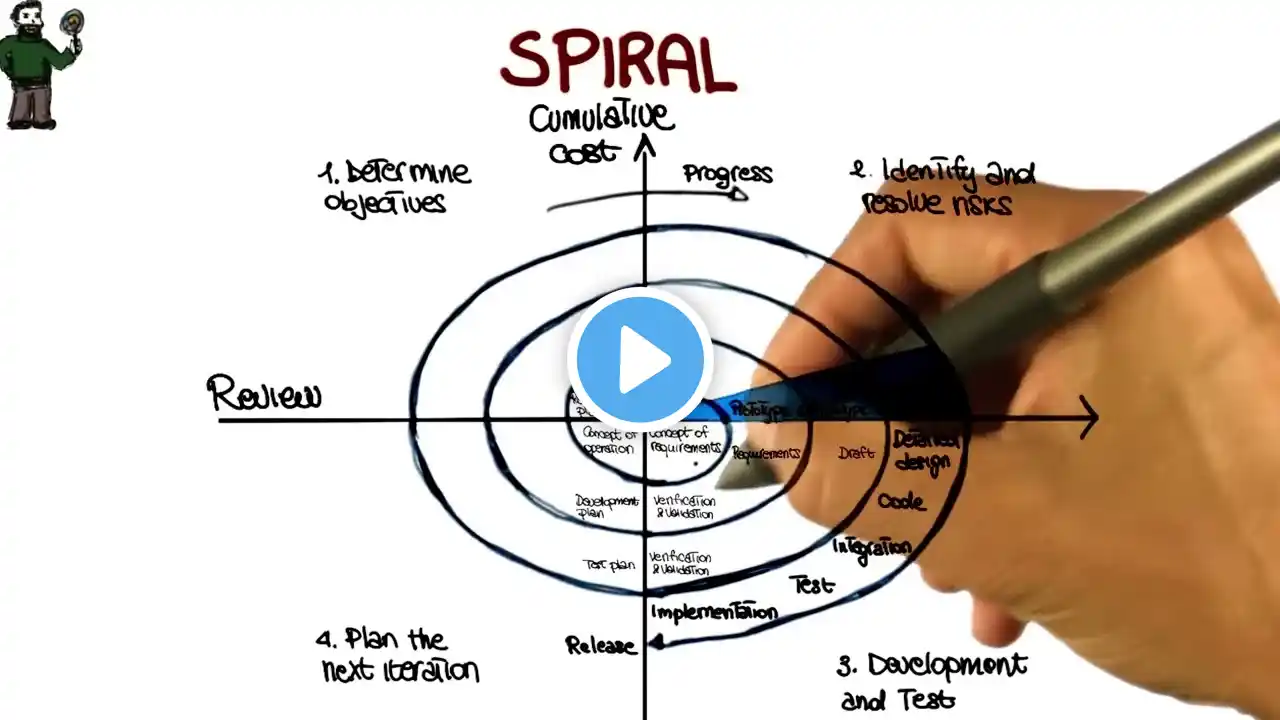

Evolutionary Process Models Evolutionary models are iterative. They are characterized in a manner that enables you to develop increasingly more complete versions of the software. Prototyping Often, a customer defines a set of general objectives for software, but does not identify detailed requirements for functions and features. In other cases, the developer may be unsure of the efficiency of an algorithm, the adaptability of an operating system, or the form that human-machine interaction should take. In these, and many other situations, a prototyping paradigm may offer the best approach. Regardless of the manner in which it is applied, the prototyping paradigm assists you and other stakeholders to better understand what is to be built when requirements are fuzzy. The prototyping paradigm begins with communication. You meet with other stakeholders to define the overall objectives for the software, identify whatever requirements are known, and outline areas where further definition is mandatory. A prototyping iteration is planned quickly, and modeling (in the form of a “quick design”) occurs. A quick design focuses on a representation of those aspects of the software that will be visible to end users (e.g., human interface layout or output display formats). The quick design leads to the construction of a prototype. The prototype is deployed and evaluated by stakeholders, who provide feedback that is used to further refine requirements. Iteration occurs as the prototype is tuned to satisfy the needs of various stakeholders, while at the same time enabling you to better understand what needs to be done. The prototype can serve as “the first system.” The one that Brooks recommends you throw away. But this may be an idealized view. Although some prototypes are built as “throwaways,” others are evolutionary in the sense that the prototype slowly evolves into the actual system. Both stakeholders and software engineers like the prototyping paradigm. Users get a feel for the actual system, and developers get to build something immediately. Yet, prototyping can be problematic for the following reasons: Stakeholders see what appears to be a working version of the software, unaware that the prototype is held together haphazardly, unaware that in the rush to get it working you haven’t considered overall software quality or long-term maintainability. When informed that the product must be rebuilt so that high levels of quality can be maintained, stakeholders cry foul and demand that “a few fixes” be applied to make the prototype a working product. Too often, software development management relents. As a software engineer, you often make implementation compromises in order to get a prototype working quickly. An inappropriate operating system or programming language may be used simply because it is available and known; an inefficient algorithm may be implemented simply to demonstrate capability. After a time, you may become comfortable with these choices and forget all the reasons why they were inappropriate. The less-than-ideal choice has now become an integral part of the system. The Spiral Model The spiral model is an evolutionary software process model that couples the iterative nature of prototyping with the controlled and systematic aspects of the waterfall model. It provides the potential for rapid development of increasingly more complete versions of the software. Using the spiral model, software is developed in a series of evolutionary releases. During early iterations, the release might be a model or prototype. During later iterations, increasingly more complete versions of the engineered system are produced. A spiral model is divided into a number of framework activities, also called task regions. Typically, there are between three and six task regions. Figure depicts a spiral model that contains six task regions: • Customer communication— tasks required to establish effective communication between developer and customer. • Planning— tasks required to define resources, timelines, and other project related information. • Risk analysis— tasks required to assess both technical and management risks. • Engineering— tasks required to build one or more representations of the application. • Construction and release— tasks required to construct, test, install, and provide user support (e.g., documentation and training). • Customer evaluation— tasks required to obtain customer feedback based on evaluation of the software representations created during the engineering stage and implemented during the installation stage. Each of the regions is populated by a set of work tasks, called a task set, that are adapted to the characteristics of the project to be undertaken. For small projects, the number of work tasks and their formality is low. For larger, more critical projects, each task region contains more work tasks that are defined to achieve a higher level of formality.