CHAPTER 1 - Introduction to Molecular Regulation and Cell Signaling in Embryology

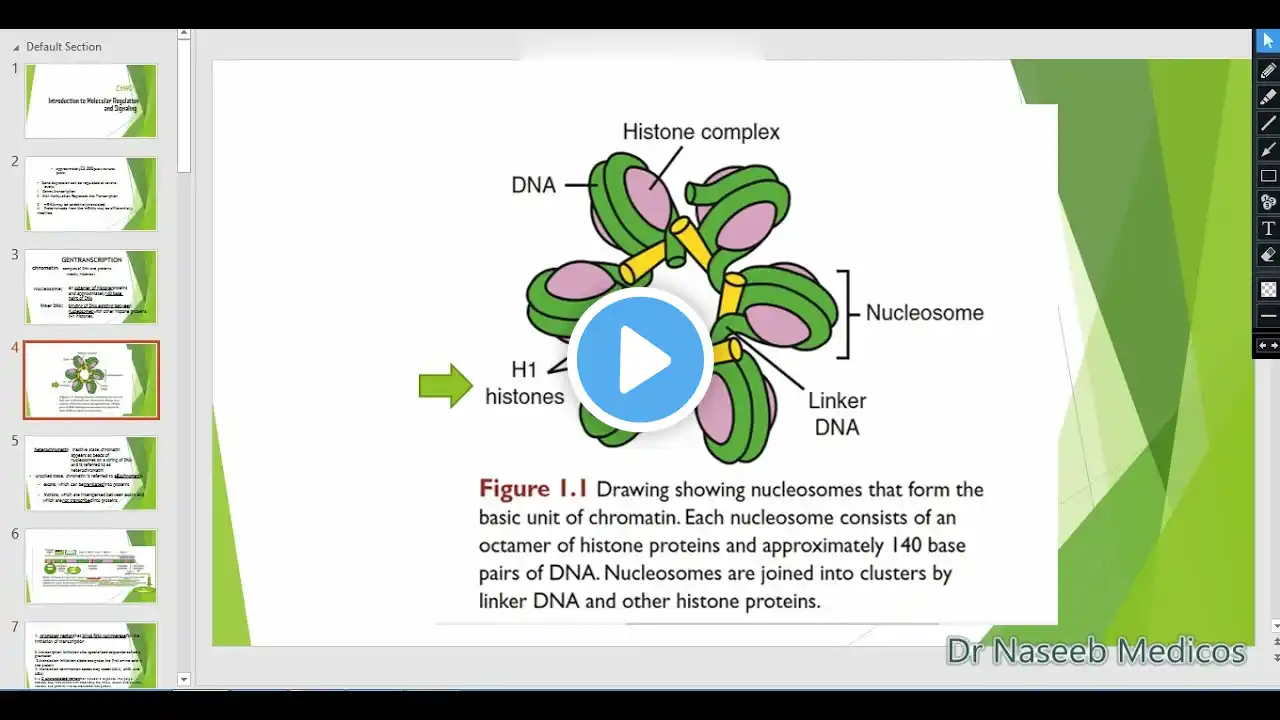

LANGMAN'S MEDICAL EMBRYOLOGY CHAPTER 1 The study of embryology has advanced significantly, moving from anatomical observation to sophisticated technological and molecular investigation, enhancing the understanding of normal and abnormal development. Molecular Regulation and Gene Expression Embryonic development is directed by genomes containing approximately 23,000 genes in humans, although due to various regulatory levels, these genes code for approximately 100,000 proteins. This disproves the one gene—one protein hypothesis. Genetic information is encoded in DNA within genes, which reside in chromatin, a complex of DNA and proteins, primarily histones. The basic unit of chromatin is the nucleosome, consisting of a histone octamer and about 140 base pairs of DNA. When DNA is tightly coiled as beads of nucleosomes, it is inactive and called heterochromatin. For transcription to occur, DNA must uncoil into euchromatin. A typical gene contains exons (translated into proteins) and introns (interspersed untranslated regions). Regulation occurs at multiple levels, including differential transcription, selective RNA processing, selective translation, and differential protein modification. Transcription Regulation: Transcription begins when RNA polymerase binds to the promoter region (usually containing the TATA box). This binding requires transcription factors, which have specific DNA-binding and transactivating domains that regulate transcription. Enhancers are regulatory elements that bind transcription factors to control promoter efficiency and the rate of transcription; they can reside far from the promoter. Enhancers that inhibit transcription are called silencers. Transcription can also be repressed by DNA methylation of cytosine bases in promoter regions. This mechanism is responsible for gene silencing, such as in X chromosome inactivation in females, and genomic imprinting, where only the paternal or maternal gene is expressed. Methylation silences DNA by inhibiting transcription factor binding or stabilizing nucleosomes, keeping the DNA tightly coiled. Post-transcriptional and Post-translational Regulation: The initial gene transcript, nuclear RNA (nRNA), contains introns that must be removed via splicing. Alternative splicing, carried out by spliceosomes (complexes of small nuclear RNAs and proteins), removes different introns to produce multiple proteins, called splicing isoforms (or splice variants), from a single gene. Additionally, proteins undergo posttranslational modifications (e.g., cleavage or phosphorylation) that affect their function and activation. Cell-to-Cell Communication and Induction Organ formation relies on interactions between cells and tissues, often through induction, where one group of cells (the inducer) causes another (the responder) to change its fate. The responder’s capacity to react is called competence, which requires a competence factor. Many inductive interactions are epithelial—mesenchymal interactions. Cell-to-cell signaling is achieved via two main types of interactions: 1. Paracrine interactions: Use diffusable proteins, called paracrine factors or Growth and Differentiation Factors (GDFs), that act over short distances. 2. Juxtacrine interactions: Do not involve diffusable proteins but rely on cell surface proteins interacting with adjacent cells, extracellular matrix ligands binding to receptors (like integrins), or direct transmission via gap junctions. Signal Transduction Pathways Paracrine factors act through signal transduction pathways involving a ligand (signaling molecule) and a receptor. Receptors typically span the cell membrane. Ligand binding causes a conformational change, often activating the receptor’s cytoplasmic domain, usually conferring kinase (enzymatic) activity. This leads to a phosphorylation cascade of proteins that ultimately activates a transcription factor, regulating gene expression. Pathways are often interconnected, exhibiting redundancy that helps compensate for the loss of specific signaling proteins. Major Signaling Factor Families (GDFs): The four major GDF families regulating development are Fibroblast Growth Factors (FGFs), WNT proteins, Hedgehog proteins, and the Transforming Growth Factor-ß (TGF-ß) Superfamily (which includes Bone Morphogenetic Proteins or BMPs). Non-protein molecules, such as neurotransmitters (e.g., serotonin, norepinephrine), also function as paracrine ligands. Key Signaling Pathways for Development: 1. Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) Pathway: SHH is considered close to a "master morphogen". It is involved in regulating development across numerous systems (e.g., vasculature, midline, limbs, organs). 2. Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) Pathway: This is the noncanonical WNT pathway. 3. Notch Pathway: This is a juxtacrine signaling pathway that requires cell-to-cell contact. A transmembrane ligand (DSL family) binds to the Notch receptor, causing the receptor to be cleaved.